Abortion and maternal mortality

Filip Furman

1. Introduction

In the international arena, experts often make a particular thesis statement, later on adopted and repeated by some politicians and opinion leaders, assuming that abortion may be a solution to high maternal mortality observed in the underdeveloped and intermediate countries. According to the United Nations publication titled Reproductive Health Policies 2017, “[u]nsafe abortion is one of the leading causes of maternal death”. It is also stated that in the countries of less developed regions, such as Africa and Oceania, many of the maternal deaths could be prevented “through better access to sexuality education, contraceptive information and supplies, and safe abortion services and post-abortion care (...)”.

The purpose of this article is to study the aforementioned correlation between legal access to abortion and maternal mortality in one hundred and seventy-five countries all over the world, based on the data analysis included in the World Bank and World Health Organization databases.

2. Maternal mortality: definition and methodological limitations

According to the World Health Organization, maternal mortality is “the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and site of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management but not from accidental or incidental causes” . Therefore, due to such a definition of maternal death, the mortality ratio includes mortality during or as a result of an abortion. In such a case, attempts to persuade less developed countries to use abortion as a remedy for improving the maternal mortality ratio seems to be a mephistophelian measure: broader access to in-clinic abortion may actually contribute to lowering the statistics denominated “maternal mortality ratio”. Thus, it does not imply a lower maternal mortality but peri-abortion mortality, which is not the same, however, the authors of this ratio seem not to notice the difference. The lack of differentiation while collecting statistical data misleads decision-makers and, further on, the public. Nevertheless, that rate is used in the international statistics involving most countries in the world, so for practical reasons, I have to consider it sufficient.

Moreover, it should be stressed that abortion is entirely banned in almost sixty countries in the world, however, the UN does not give it such a status due to the fact that those countries allow abortion in order to save a mother's life, even if the procedure threatened the life of her unborn child. Such cases are often referred to as “saving woman's life as grounds for abortion”. Nonetheless, such a denomination does not seem right because saving a woman's life is not equal with a consent to procedures which are aimed at taking child's life. It is tantamount to undertaking healing procedures in order to save woman's life, even if they led to bodily harm or disorder of health of the conceived child. There is a great diversity in such procedures, including Caesarian section in preterm labours conditioned by the mother's health state. In accordance with K. Jusińska et al.: “(…) acting with the purpose of sacrificing an interest protected by the law in order to rescue another interest of such characteristics, provided the interest being rescued represents greater or equal value in comparison to the interest sacrificed (proportionality of the interests protected by the law)” does not mean abortion is permissible.

Another erroneous, and, as a matter of fact, sophistic action performed by the promoters of abortion as a remedy lowering maternal mortality, consists in exposing spurious relationships, that is situations in which, based on the co-occurrence of two variables, it is concluded that one variable results from the other, ignoring the potential influence of a third variable which influences both the first and the second variable and constitutes the actual reason of the phenomenon observed. In other words, the variables are causally related but they do not result one from the other. For instance, “the bigger the fire, the more fire fighters”, ergo: “increasing the number of fire fighters provokes an increase in the fire volume” or better still: “fire fighters cause fires”. Such reasoning is clearly absurd. However, not each and every example is as obvious as the above-expressed one. In the case of abortion the situation is similar. As a matter of fact, according to the image created by the available worldwide statistics, the countries with the highest maternal mortality ratio mainly include states with rather strict abortion laws. Nevertheless, it does not necessarily mean that restrictions on the availability of abortion provoke the growth of this ratio. In fact, frequently there are other variables which are the actual reason of the relationship observed. In the case of maternal mortality, it may be due to the general access to medical services and their quality, as well as the standard of living in a given society.

In the present analysis, I would like to try to answer the question of whether the rigorousness of the abortion law affects maternal mortality. If so, I would like to determine the extent and direction of the influence. If not, I hope to find other factors that may be used to explain the differences in the maternal mortality ratio observed between countries.

3. Data sources and analysis methods

The present analysis has been carried out based on the secondary data. The data regarding maternal mortality, health expenditure as a percentage of GDP, health expenditure per capita and life expectancy at birth were collected from the World Bank and World Health Organization databases. The analysis includes the most recent available data from 2017.

The data regarding the access to abortion come from the United Nations information catalogue World Abortion Policies 2013. That source is clearly limited due to the fact that it may be partially outdated. Another limitation presented by the abovementioned information catalogue is the fairly simplified way in which it presents the reasons for the legal permission of abortion in different countries (however, in the case of such a broad report, the simplification seems to be understandable). Nonetheless, according to the best of the author's knowledge, the catalogue remains the most recent source of institutionally verified data presenting worldwide regulations in an aggregate manner, making it possible to carry out the analysis.

The analysis includes the following factors:

• maternal mortality ratio (MMR) per 100,000 live births;

• health expenditure as a percentage of GDP of a given country;

• health expenditure per capita in USD;

• life expectancy at birth;

• region of the world;

• abortion availability.

The classification of the regions of the world with their respective countries, has been drawn on the basis of the UN geoscheme, a system used in the United Nations statistics which divides the countries of the world into regional and subregional groups. The present analysis involves subregions. To be precise, it includes twenty-two groups as follows: North Africa, Central Africa, South Africa, East Africa, West Africa, North America, Central America, Caribbean, South America, Central Asia, South Asia, Southeast Asia, East Asia, West Asia, Northern Europe, Southern Europe, Eastern Europe, Western Europe, Australia and New Zealand, Melanesia, Polynesia, and Micronesia.

Abortion availability has been defined in accordance with the definition provided by the aforementioned UN document, World Abortion Policies 2013. In that publication, abortion availability includes seven categories of a binary character: the abortion of a given category is either permissible in a given country or it is not. The categories are as follows (legal grounds on which abortion is permitted): to save a woman's life, to preserve a woman's physical health, to preserve a woman's mental health, in case of rape or incest, because of foetal impairment, for economic or social reasons, on request.

The data analysis has been conducted with the traditional descriptive statistics methods as well as elements of inductive statistics (statistical tests for studying the relationships between variables, and the differences between groups).

Descriptive statistics methods included:

1. a chart with one variable;

2. contingency tables (three variables).

Inductive statistics methods included:

1. one-way analysis of variance ANOVA;

2. coefficient of determination R squared.

The analysis was performed in the IBM SPSS Statistics programme.

4. Results

4.1. Maternal mortality vs. abortion availability: comparison to other factors

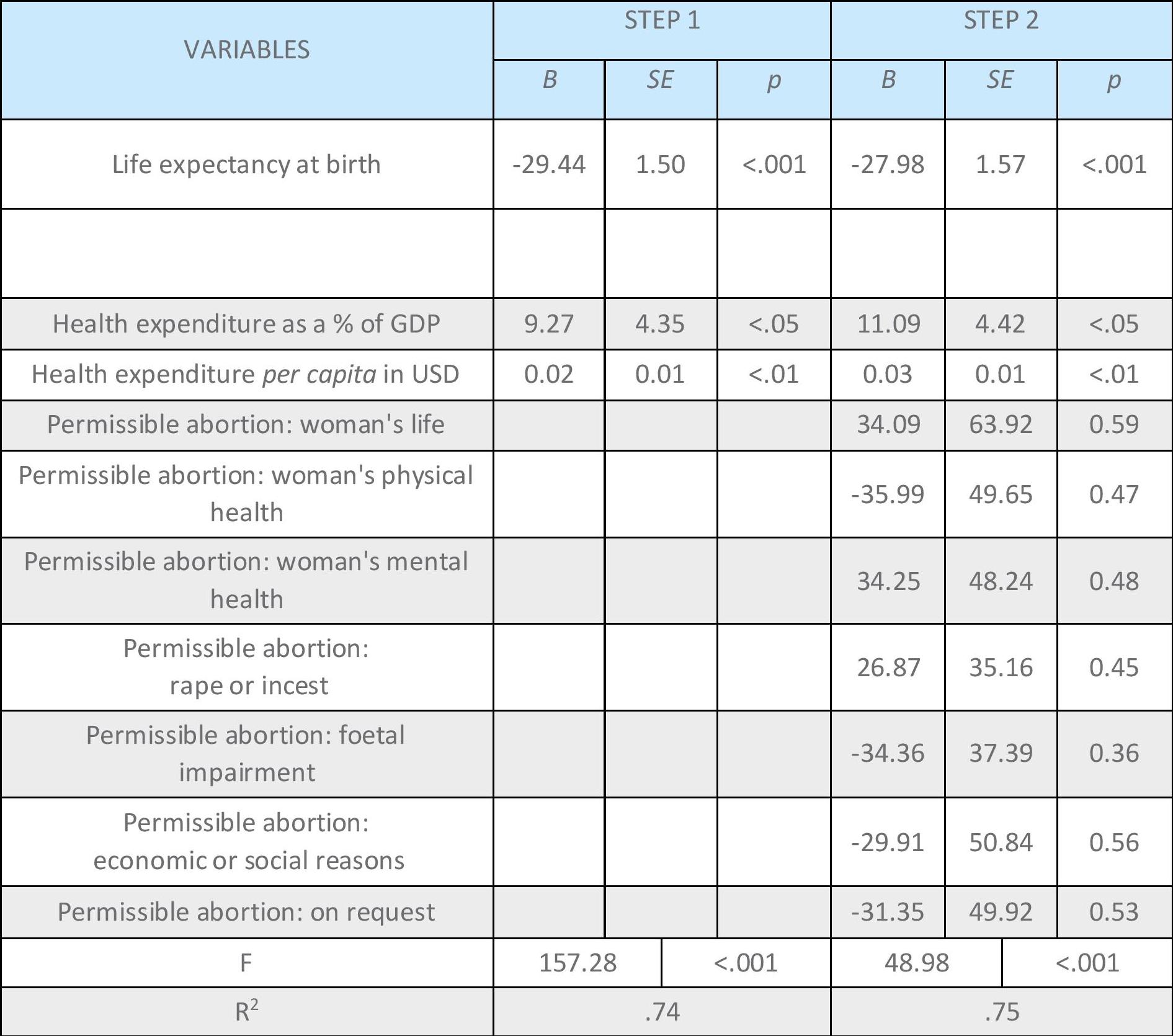

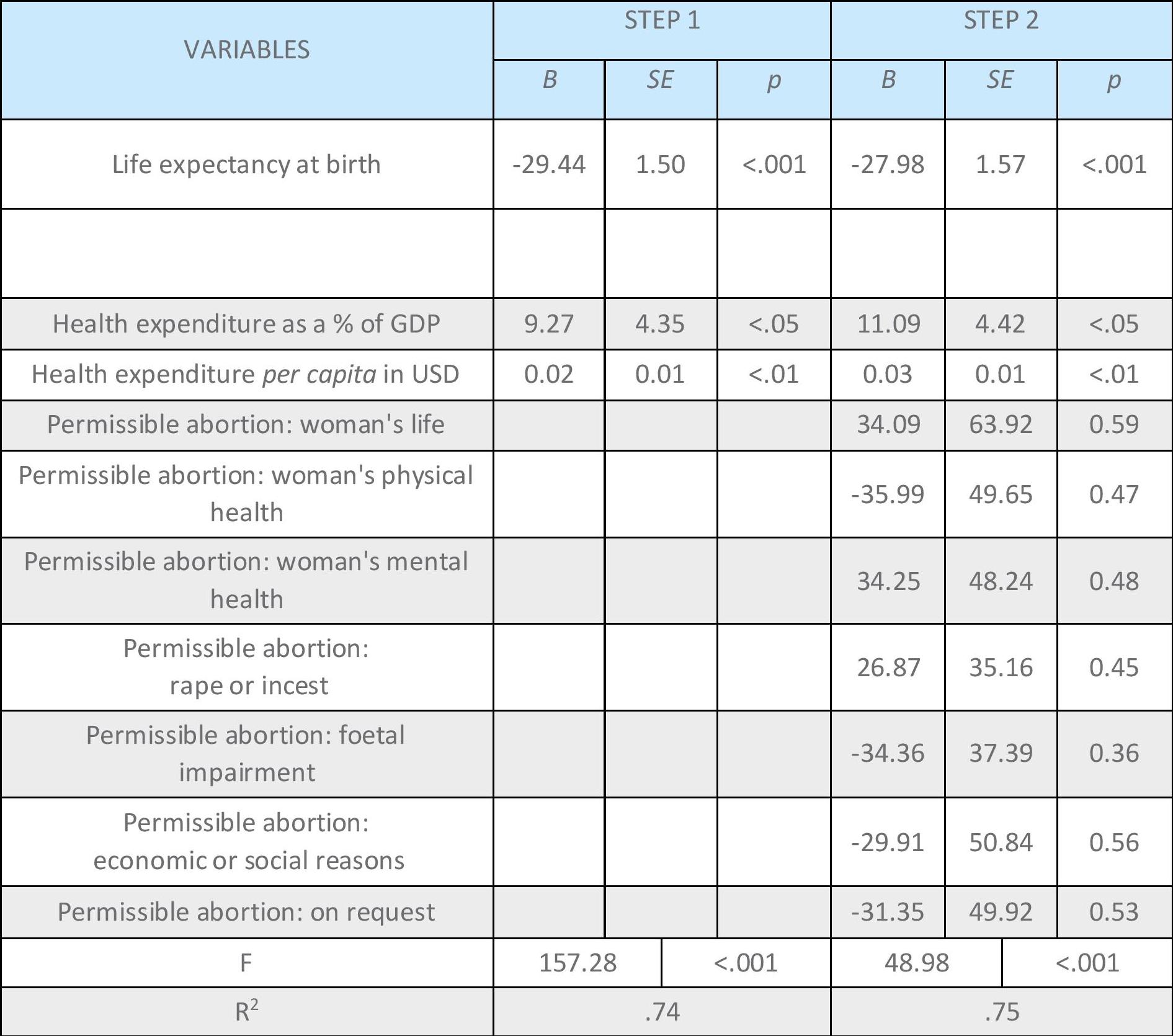

In order to examine the relationship between abortion availability (studied upon the legal permission of the procedure) and maternal mortality, a two-step hierarchical linear regression was carried out (Table 1). In pursuance of determining abortion as one of the factors affecting maternal mortality, it was compared with other ratios concerning the population's health: life expectancy at birth, health expenditure as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product, and health expenditure in USD absolute value per capita.

[Table 1. Maternal mortality predictors: hierarchical regression results]

At the first step of the analysis conducted, the following variables were introduced: life expectancy at birth, health expenditure as a percentage of GDP, and health expenditure per capita in USD. At the second step, the cases of permissible abortion based on the seven categories included in the UN classification were added: saving a woman's life, preserving a woman's physical health, preserving a woman's mental health, in case of rape or incest, foetal impairment, economic or social reasons, on request.

The result showed that the best maternal mortality predicator, among all taken into account, is life expectancy at birth. A strong negative relationship between those variables was shown.

The R-squared coefficient of determination amounted to 0.74 at the first step, and 0.75 at the second one.

This means that the introduction of variables regarding permissible abortion improved the (already very high) model accuracy only by 0.01. What is more, the salience of the obtained results for life expectancy at birth, health expenditure as a percentage of GDP, and health expenditure per capita in USD achieved very good levels at both steps, from <.05 up to <.001, depending on the variable. Whereas variables regarding abortion availability turned out to be statistically irrelevant in any case.

4.2. Maternal mortality vs. abortion availability: comparison between countries

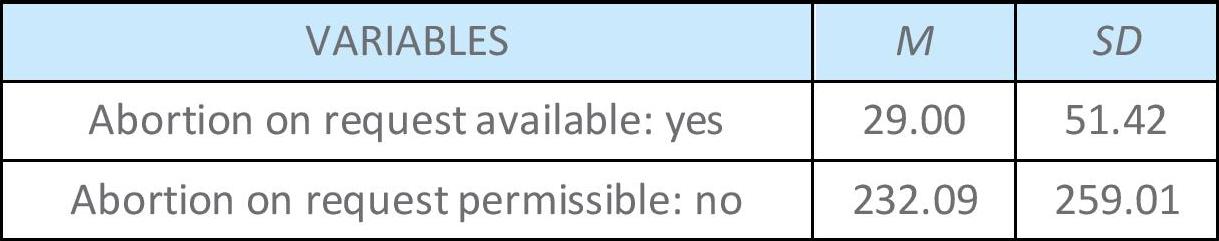

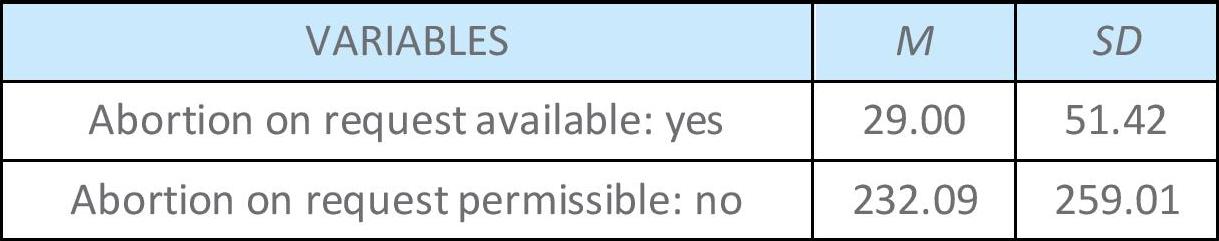

Abortion on request was analysed separately. A comparison of the averages for countries allowing and not allowing abortion on request shows that maternal mortality in countries allowing abortion on request is many times lower than in countries not allowing abortion procedures on this ground (Table 2).

[Table 2. Maternal mortality and abortion on request availability: worldwide averages comparison]

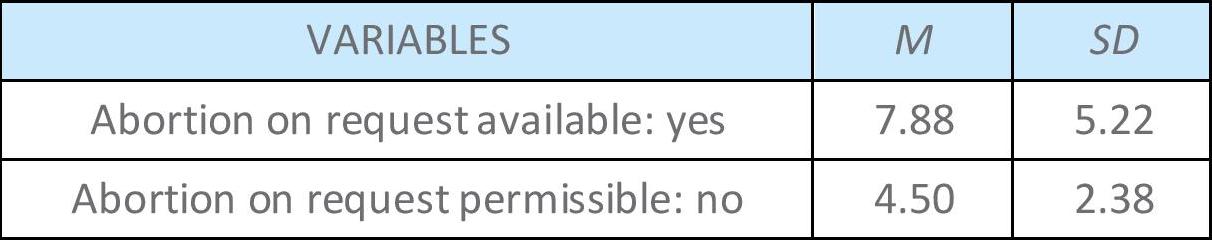

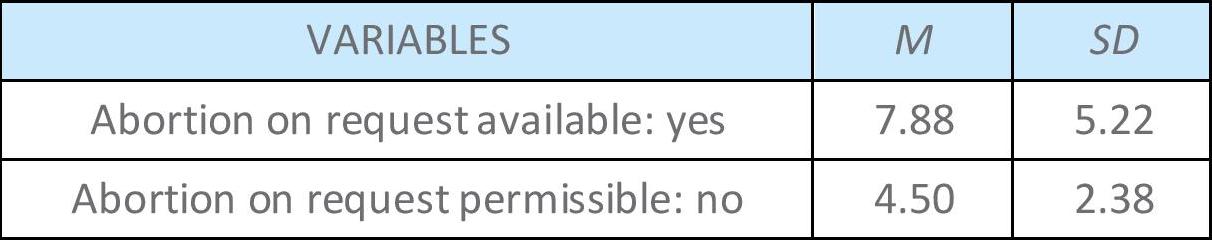

However, comparing maternal mortality between countries from different cultural fields and of clearly different levels of development raises considerable methodological doubts. In order to verify the observed tendency, a corresponding analysis was performed only for European countries (Table 3).

[Table 3. Maternal mortality and permissible abortion on request: comparison of the European averages]

The results of the analysis of maternal mortality and permissible abortion on request within Europe indicate an opposite tendency in comparison to the general global tendencies. The average MMR in the European countries, which do not have legislation allowing abortion on request is lower than in the countries which allow such a procedure.

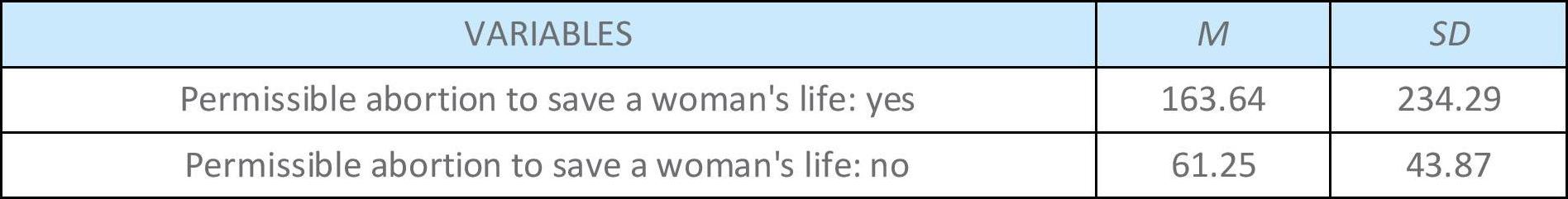

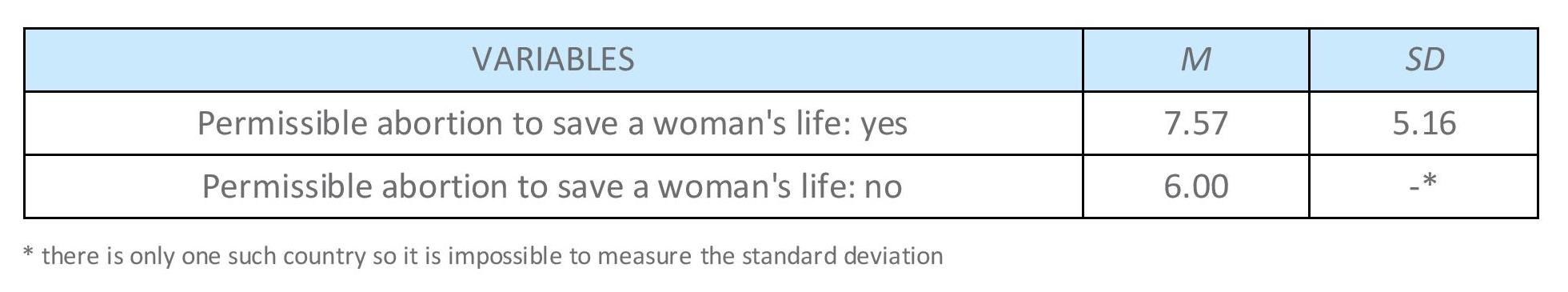

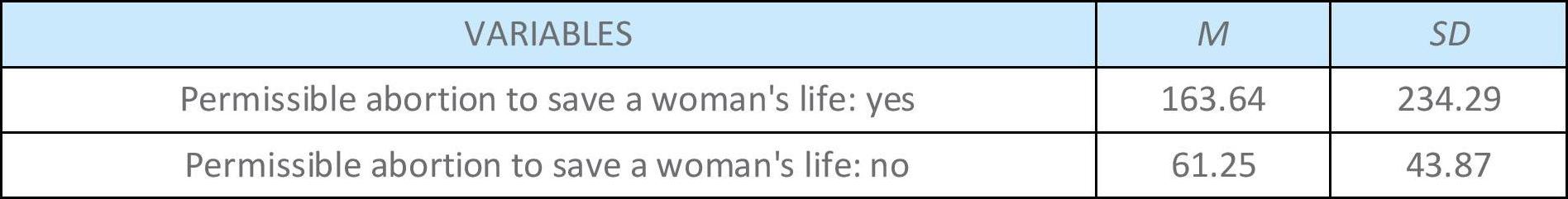

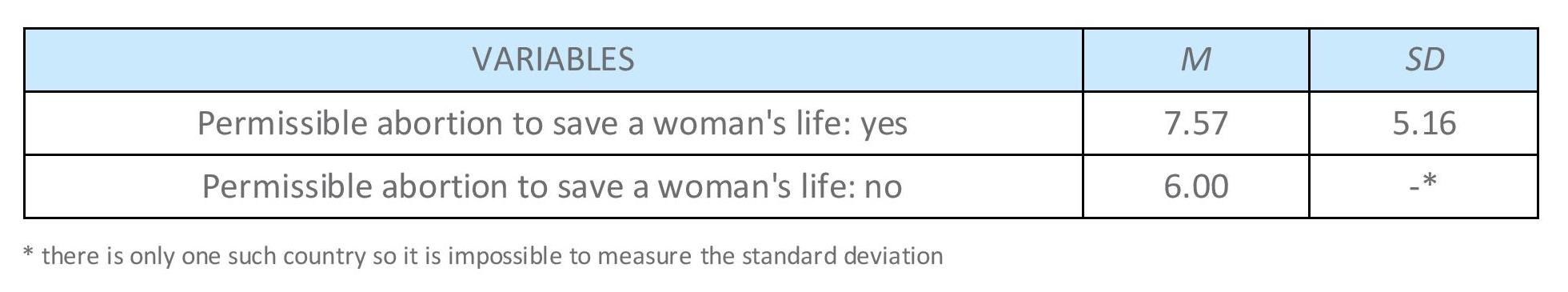

Additionally, an analysis was performed of the reverse situation, that is, a total ban on abortion, including one to save a woman's life, to compare tendencies both in the world (Table 4) and in Europe (Table 5).

[Table 4. Maternal mortality and permissible abortion to save a woman's life: worldwide averages comparison]

[Table 5. Maternal mortality and permissible abortion to save a woman's life: comparison of the European averages]

Therefore, the compared averages show that in the countries which do not allow abortion by law, the average MMR is significantly lower than in the countries allowing it. However, due to the small number of countries which entirely ban abortion (N=4), the obtained results may raise methodological doubts. Nevertheless, they shall be kept in mind because they suggest a phenomenon opposite to the one described in the aforementioned UN document.

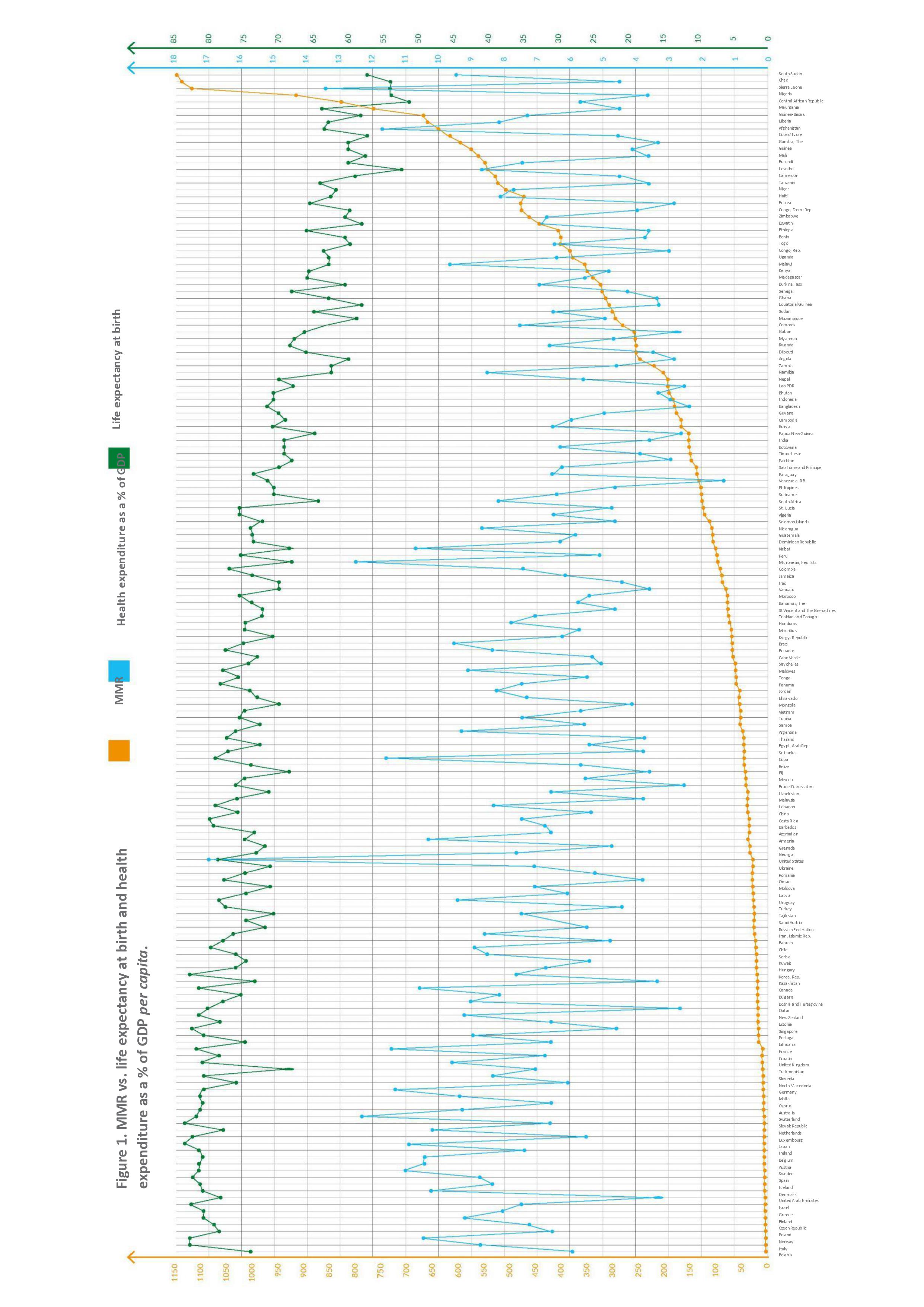

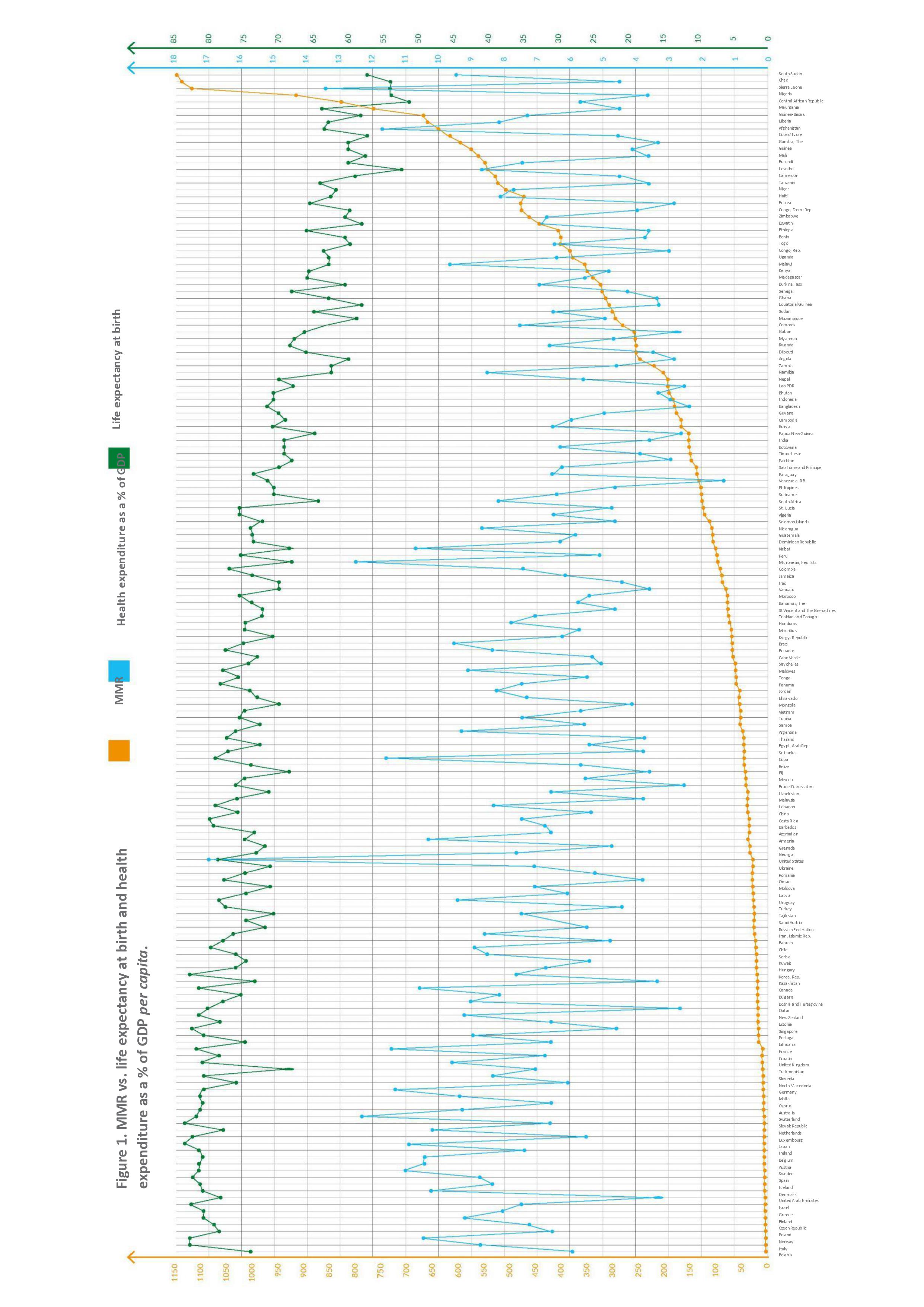

When analysing maternal mortality in particular countries, it should also be noted that the maternal mortality compared to life expectancy at birth, and the health expenditure as a percentage of GDP of a given country make it evident that life expectancy (one of the best indicators of the general standard of living in a country) clearly presents a negative correlation with MMR: when life expectancy increases, maternal mortality ratio decreases (Figure 1). Such an explicit relationship is not observed in the case of the health expenditure as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product of a given country.

[Figure 1. MMR vs. life expectancy at birth and health expenditure as a % of GDP per capita]

4.3. Maternal mortality vs. abortion availability: regional differentiation

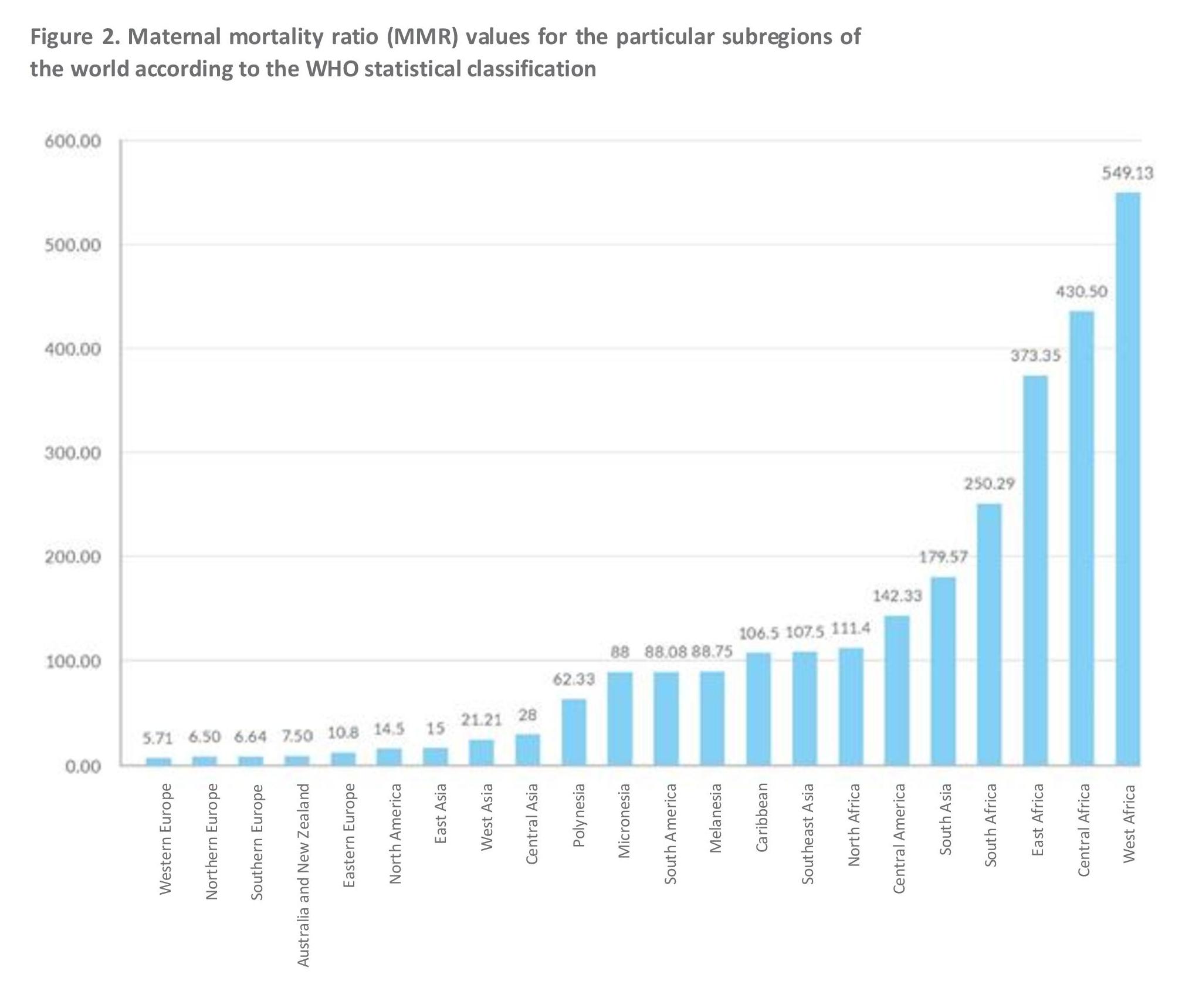

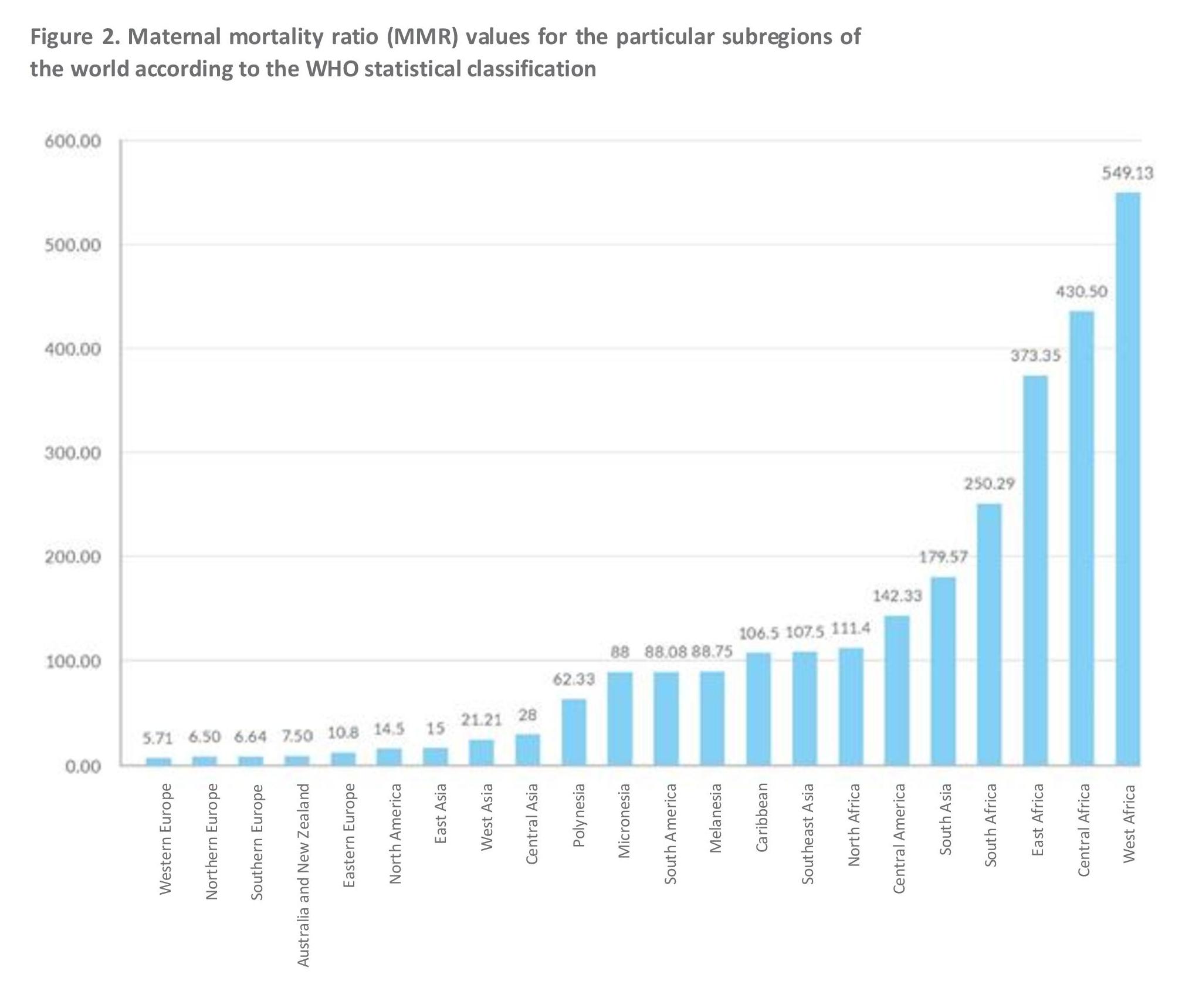

The maternal mortality ratio is significantly different, depending on the given region of the world (Figure 2). If one orders the available data from the smallest to the largest MMR, it forms a continuum that may be defined, in simple terms, as the “Old World and Western Culture”, the “New World and the Atlantic basin”, the “Pacific basin” and “Africa”.

The observed regional differentiation is fairly big worldwide. It is important to stress the gulf between Europe and Africa en general, especially between Western Europe (average MMR=5.71) and West Africa (average MMR=549.13). The maternal mortality ratio is nearly a hundred times higher in the latter region!

[Figure 2. Maternal mortality ratio (MMR) values for the particular subregions of the world according to the WHO statistical classification]

5. Discussion of results, summary and conclusions

In a regression analysis performed for the following variables “life expectancy at birth” and “maternal mortality”, coefficient B amounted to -29.44. That indicates a strong, negative correlation between life expectancy at birth and maternal mortality. Such a result means that the lower the life expectancy at birth, the higher the maternal mortality. It confirms the intuitive assumption that maternal mortality is related to the general standard of living (which is composed of many variables, resulting in a longer lifetime).

At the same time, in terms of the maternal mortality correlation with health expenditure as a percentage of GDP, the coefficient B amounted to 9.27. Therefore, the increase in maternal mortality is correlated with the increase in health expenditure as a proportion of GDP in a given country. Such an observation may seem surprising at first. However, it only means that health expenditure is a way bigger burden for poorer countries than for rich ones, despite the difference in the quality and availability of medical services. In no case, should this coefficient be interpreted as an argument for reducing health expenditure.

Just as the abovementioned relationship between health expenditure and maternal mortality should not be interpreted as a case for reducing health expenditure, the relationship between allowing abortion and the MMR ratio should not be interpreted as a case for increasing access to this procedure. The results of the analysis of the correlation between maternal mortality and permissible abortion in all cases comprised in the UN document apparently show that maternal mortality ratio raises in certain cases of permissible abortion, whereas in other cases it decreases. Nonetheless, these results are highly error-burdened: there is a positive correlation between abortion permissible to save a woman's life and MMR (B=34.09; SE=63.92), a negative correlation in the case of abortion permissible to save a woman's physical health (B=-35.99; SE=49.65), positive in terms of saving a woman's mental health (B=34.25; 48.24), also positive in case of rape or incest (B=26.87; SE=35.16), negative in the case of foetal impairment (B=-34.36; 37.39), negative in terms of economic or social reasons (B=-29.91; SE=50.84), and also negative in the case of abortion on request (B=-31.35; SE=49.92). Therefore, none of those correlations was statistically relevant. Moreover, in the first step of the conducted analysis, which did not include permissible abortion, the R-squared coefficient of determination amounted to 0.74, and in the second step, 0.75. This means that the introduction of variables regarding permissible abortion has improved the model accuracy only by 0.01. Thus, the results of the study support the assumption that there is no relationship between permissible abortion and maternal mortality.

However, the comparison of the average maternal mortality rate in the countries which allow abortion on request (M=29.00) and those which do not allow abortion in such a case (M=232.09) could serve as a rhetorical argument for the need of making abortion on request legally permissible, despite the lack of an actual relationship demonstrated in the previous step. But if one views the difference only in the region of the world where the standard of living as well as the quality and availability of healthcare is en mass the highest in the world, that is Europe, one observes an opposite tendency: in the countries which allow abortion on request, average maternal mortality amounts to 7.88, whereas in the countries which do not allow it, 4.50. Additionally, by looking at the countries with the most rigorous abortion law, where the procedure is not legally allowed, regardless of the premises, one will notice that both in Europe and in the whole world, the average maternal mortality is lower in the countries which entirely ban abortion than in the remaining ones. Naturally, this does not prove directly that abortion should not be allowed. However, it shows how remote the relationship between abortion and maternal mortality is. Those four countries where abortion is not allowed by law do not include the poorest countries with a low standard of living and poor healthcare, which overstate considerably the average MMR in the group of countries allowing abortion. Maternal mortality and permissible abortion are connected as if they were two flowers in one garden. They grow in the same ground, they are exposed to the same rains and if there is drought, they both may die back, but it does not mean we can take care of only one of them and the other one will flourish too. There is no cause-and-effect relationship between them.

It should be stressed that, in many cases, performing an abortion on an ill woman may deteriorate her health condition. According to a Dutch study based on population registers from 1980–2002, the risk of death after an abortion before the twelfth week of pregnancy is almost twice as high as the risk of maternal death than delivering a baby. The risk in late-term abortions turned out to be even greater, whereas the risk after spontaneous abortion was smaller.

The division of countries into regions, in accordance with the geoscheme used in the UN statistics and the further regional classification by maternal mortality rate, makes it evident that the gulf between the “Old”, “New” and “Third World” remains huge. The difference in maternal mortality between the region of the lowest MMR, Western Europe, and the highest, West Africa, is almost a hundredfold! Thus, as Poles and Europeans, we live in a privileged region of the world. If we want the poorer countries to be privileged too, instead of wasting our resources on unnecessary abortion and its promotion, we should use them to help pregnant women in the “Third World” countries, so that they can give birth in safe and decent conditions.

To sum up, the results of the conducted analysis show that:

-

Maternal mortality is highly diverse depending on the country, which squares with geocultural diversity;

-

The improvement (that is reduction) of the maternal mortality ratio is influenced rather by the general standard of living in a given country than direct health expenditure;

-

Broader access to abortion services cannot be a measure for lowering maternal mortality;

-

Using statistical indicators without taking into account knowledge about the cultural and economic context of a given region and with no medical research has little methodological value and should not be a basis for the international agenda in the formulation of law benchmarks for other countries.